In the face of declining oil production and economic challenges, Nigeria’s oil industry stands at a critical juncture. The urgent need for efficiency and cost reduction has never been more apparent. This article explores the transformative potential of improving drilling performance and reducing well delivery costs, highlighting the significant opportunities and strategies that can drive the industry forward and secure its long-term sustainability.

To quote Joel Barker in “The Business of Paradigms,” “It’s so easy to say no to a new idea. After all, new ideas cause change; they disrupt the status quo. They take people out of their comfort zones and create uncertainty… Plus, it is less work to do things the way we have always done it. Less work, maybe. Costly, definitely.”

New ideas are resisted from greasy rig floors in the Niger Delta Swamps to cushy business offices and conference rooms in regulators’ offices in Abuja, each with very prohibitive costs of inaction.

Yet it’s business as usual in Nigeria’s oil industry despite current economic realities in the country, which provide the impetus for a radical transformation of its cost base. Pulling the ailing economy from the brink calls for a radical improvement in efficiency within its mainstay industry. Dwindling daily production and significantly reduced foreign exchange earnings and foreign reserves establish the urgency to drive down the unit cost per barrel of oil produced.

Simply stated, today’s ‘good’ is tomorrow’s ‘not good enough,’ and what sets us apart today will be the baseline tomorrow. The future belongs to those who act with urgency and foresight.

A Huge, Yet Untapped Opportunity

Successful upstream operations are underpinned by the ability to balance the trio of cost, schedule, and production and maximize NPV, i.e., produce the most barrels in the quickest manner possible at the cheapest mean cost across a portfolio of assets.

Incremental improvement in well delivery (drilling & completion) efficiency in the US characterized the shale oil boom, which effectively began in 2007. Efficiency gains cut well costs by a third and reduced cost per barrel by 75% in the decade between 2007 and 2017. In effect, America became an oil and gas powerhouse within this period, doubled US shale production, and tripled total daily oil output.

In Nigeria, the oil and gas industry is the largest revenue contributor to the Nigerian economy, but production has declined by 40% from 2010 to date. Declining oil production presents major revenue challenges and precipitates chronic macroeconomic crises in the short to medium term.

Reducing unit production costs by driving down well delivery costs presents an untapped opportunity to increase government earnings and reduce its fiscal deficit.

Being the most complex, costly, and highly specialized upstream development activity, which easily accounts for up to 60% of oilfield development CAPEX, drilling presents a unique opportunity to reduce the cost of oil production.

For this reason, in the early eighties, drilling engineers and other personnel operating in the UK North Sea recognized the need to learn from each other and compare performances across each other’s drilling operations. This led to the formation of the Drilling Performance Review (DPR) in 1989, a drilling benchmarking club. The majority of international operators who are value-driven continue to subscribe to the DPR to this day for the inherent benefit to their global operations and enterprise financial performance.

In general, up to 60% of drilling time goes to non-productive time (NPT) and inefficiencies, known in drilling parlance as invisible lost time (ILT). The cost of ILTs, being an invisible factor, to the Nigerian oil industry is in the order of billions of dollars overspent annually.

Improving drilling performance, therefore, is an enabler to reducing the cost of oil production. Lower drilling costs stimulate more drilling activities, which in turn increases production and reduces unit production costs.

You Can’t Improve What You Don’t Measure

Drilling performance in Nigeria is laden with tremendous inefficiencies. An indicative benchmark of an average Nigerian and a similar North American well reveals significant underperformance in the Nigerian well as measured by days to drill a 10,000-foot well. A 10,000-foot well routinely delivered in 10 days in the US/Canada could take as long as 85 days in Nigeria. This disparity is surmised to be the cause of the consistently high well delivery cost in Nigeria. Disproportionately long well durations delay time to market (deferred production), reduce project NPV, and costly wells reduce the number of profitable opportunities, which in turn reduces rig activities and associated demand for services.

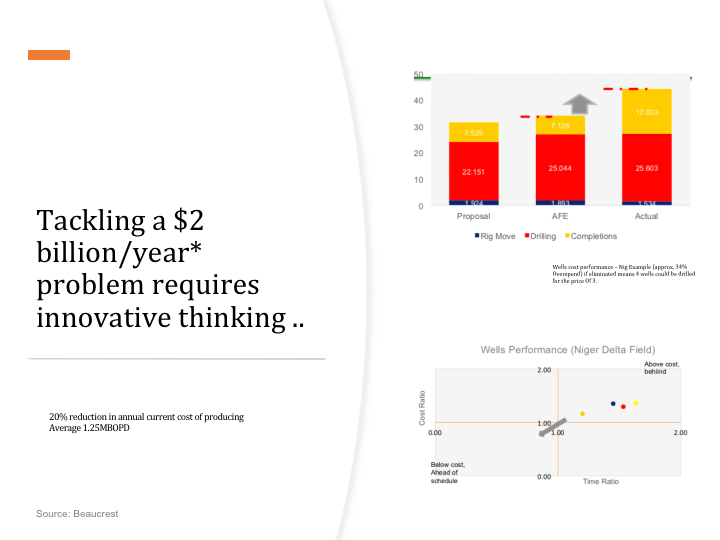

By top-down estimates, the industry spends circa $11.4 billion to produce 1.25 million barrels daily and approximately $6 billion in drilling wells. A 30% performance gap between the authorized expenditure (budget) and actual costs, as gleaned from an analysis of Nigerian wells, represents a $1.8 billion a year opportunity.

The relentless pursuit of excellence in well delivery begins with establishing key indicators, which must be tracked with rigor, and provides an indication of drilling performance and efficiency trends.

An excellent drilling efficiency metric commonly tracked is the spend ($) per reservoir foot of hole. US-based oil services research firm Spears & Associates, Inc. looked at this metric in US land operations from 2006 to date, showing the cost of a foot of exposed reservoir falling by 75% in over a decade when considering what was paid to the contract driller. Similarly, the directional driller cost per exposed reservoir foot fell from $45 to $35, a decrease of 25%.

In addition to the reduced cost per barrel, other implications of drilling efficiency gains break down as follows:

- The price of contracting a rig in 2006 is now the price of four rigs in 2023, i.e., four rigs can be operating today for what it cost 16 years ago.

- Four rigs drilling means 300 oilfield workers employed (instead of 75 on one rig). This is direct labor. We know how many mouths get fed when 300 workers are employed instead of 75.

- Four rigs working means a higher rig count overall. A higher rig count means more services contracted, e.g., wireline, mud logging, casing, and cementing crews, etc. This means 4X the number of casing running crews, mud logging crews, wireline crews, etc., needed (as well as the number of mouths each of them feed). This simply means higher activity and spending in the sector.

- Four rigs working means more reservoir exposure, higher production, higher probability of new discoveries, which increases reserves, and translates to higher revenues for the country in the form of (a) increased government share of oil production and (b) increased taxes and royalties accruing to the state.

- Driving down drilling costs can make the difference between a marginal field holder’s ability to commercialize an asset.

Where There Is a Will, There Is a Way

Investments in the Nigerian oil and gas sector declined by 70% between 2017 and 2021, closely correlating with the contraction in production output. Nigeria could only attract $3 billion in investments (approximately 5% of the total investment into the sector in Africa) in the five years between 2017 and 2022 despite having 38% of the continent’s total hydrocarbon reserves. As the government pushes for more transfer of resource ownership to locals via organized acreage farm-outs and International Oil Company (IOC) divestments, Nigeria’s oil industry’s uncompetitiveness is certainly at its pinnacle.

For the sake of the industry some of us love for being the source of our livelihood, the hundreds of thousands of mouths it feeds directly, and the hundreds of millions of Nigerians it’s long-term sustainability impacts, pulling the industry (and by extension the economy) back from the brink is not optional, but a matter of feral urgency, a task which rests squarely with the industry regulatory agencies.

Tepid as the implementation has been, the Petroleum Industry Act emboldens the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) to drive cost and capital efficiency in oil industry upstream operations. A total transmutation of NUPRC’s operating philosophy from that of its predecessor agency, the DPR (not the business-as-usual approach), will be required to unlock a $2 billion a year opportunity in these critical times as the oil industry continues hemorrhaging unabated.

Local operators and IOCs continue to battle a worsening capital drought and industry contraction. Stakeholders who will be convening in the nation’s capital on the 26th and 27th of June at the NUPRC-organized industry consultative workshop will be seeking guidance from their hosts, curious to learn what fresh ideas will be unveiled that will provoke the cataclysmic actions to stem the existential crisis confronting the sector.

Current realities provide the impetus to institute a deliberate drilling cost reduction initiative in Nigeria. Effort should be made to sustainably reduce well delivery costs across all joint ventures, sole risk, and production sharing contract (PSC) operations for the lifeline it offers to an industry literally tethering on life support.

Operators deserve insights and answers to these critical questions, which ironically can be extracted from gigabytes of drilling data in PDFs, and in thousands of hard copy folders sitting in dusty cabinets in NUPRC’s warehouses.

- Who are the Best in Class / Top Quartile Nigerian Operators across key performance metrics (drilling efficiency (speed) and cost ($)) in each terrain?

- What are the performance gaps between their own wells and the best in class wells?

- What are the causative factors for the discrepancies in performance (gap) between their wells and the best in class wells?

- What can they do to close the gaps and pull up their performance towards the best in class?

While they scratch their heads searching for answers, we recommend the regulator urgently institute performance improvement programs that leverage the latest computing technologies as well as an abundance of human capital to drive the systematic optimization of drilling programs and the entrenchment of commercial sustainability across the breadth of Nigerian drilling operations. This will serve as an economic stimulus by lowering all key metrics, including unit operating, as well as finding and development costs. It will improve the fiscal breakeven price of oil.

There is no standing still. We are either growing or dying, and since we are not growing, as established by all indices, we challenge the custodians of this atrophying industry to lead, follow, or simply get out of the way.

About the Author

Dimeji Bassir is an accomplished oil and gas executive with over twenty-five years of international experience working with multinational operators and oilfield service companies. Throughout his career, he has held various operational, consulting, and commercial roles at Chevron, Baker Hughes, Halliburton, and General Electric. Currently, Bassir leads Ofserv, an independent consultancy specializing in subsurface engineering, project management, drilling performance improvement, and reliability services. Before Ofserv, Bassir was the Country Manager for Nigeria at GE Oilfield Technology and a Drilling Reliability Consultant at GE Energy Services. He also served as a Drilling Performance Consultant for clients such as BP, Shell International, and ConocoPhillips, and held field engineering positions in both onshore and offshore drilling operations with Baker Hughes, Halliburton, and Chevron.