Luiz Fernando Toledo and

Carol Castro,BBC News Brazil, Rio de Janeiro

MAURO PIMENTEL/AFP via Getty Images

MAURO PIMENTEL/AFP via Getty ImagesNew details which have emerged in the aftermath of Brazil’s deadliest police operation are casting doubts over whether the raid really struck at the heart of one of the country’s most powerful criminal gangs, as was its stated aim.

One hundred and twenty one people, among them four police officers, were killed in the raid on 28 October in Rio de Janeiro.

The governor of Rio de Janeiro state, Claudio Castro, described the police operation as “a success”, posting a photo showing the more than 100 rifles seized by police.

But rights groups have sharply criticised the security forces pointing to the high death toll and what they have described as the “brutality” of their actions.

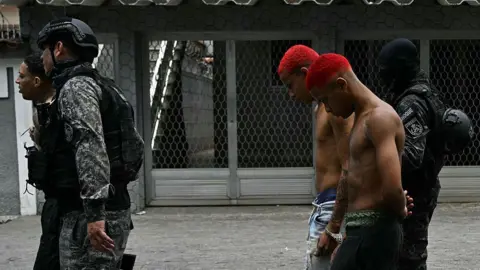

The operation was the largest ever carried out by Rio’s security forces and saw 2,500 officers deployed to the Alemão and Penha neighbourhoods.

It targeted the Comando Vermelho (Red Command) criminal gang, which rules over the nine-million-square-metre area.

Reuters

ReutersRio’s public safety secretary, Victor dos Santos, told Reuters that the goal of the operation had been to carry out scores of arrest warrants issued by prosecutors.

But when BBC Brasil cross-checked the list of the deceased published by police against the 68 names on the list of suspects provided by prosecutors, it found that none of them matched.

Local media have also pointed out that even though scores of suspects were arrested during the raid, the man considered the gang’s most powerful leader, Edgar Alves de Andrade, also known as Doca, was not among them.

“Early reports stated that the goal of the operation was to capture high-ranking leaders of the Comando Vermelho (CV),” Carlos Schmidt-Padilla, professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, told BBC Brasil.

“By that metric, it is fair to say the operation failed.”

REUTERS/Tita Barros

REUTERS/Tita BarrosAt a Senate hearing, the deputy intelligence secretary for Rio’s military police stated that the raid had had a “negligible” impact on dismantling Comando Vermelho.

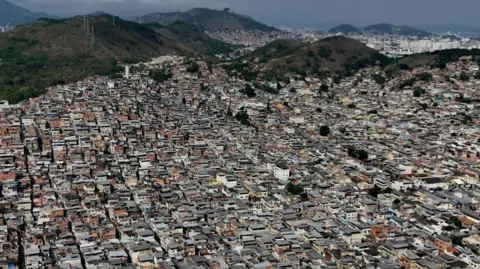

Residents of the Alemão and Penha have also told the BBC that it has done little to loosen the tight grip the CV has on their favelas.

How Rio’s gangs rule through fear and control

They said that their daily lives had barely changed since the mega-operation, describing seeing armed men roaming the community the very next day, even as the bodies of those killed were still being removed.

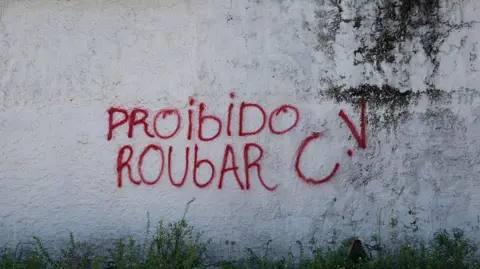

Comando Vermelho (CV) and groups like it enforce strict rules in the areas they control.

These criminal enterprises have moved beyond the sale of drugs and now hold the monopoly for the provision of gas, cable television, internet and transport.

Residents report being charged over the odds for gas cylinders, often having to pay one third more than in zones not under gang control.

Rules imposed by gang members affect everyday life.

As CV has banned cars working for ride-hailing apps from entering the favelas, locals are restricted to using motorbike taxis and vans which have been authorised by the gangs to operate there.

Even people’s clothing is policed by the gang. In 2020, residents of Penha were told not to wear Chelsea football shirts.

At the time, the jerseys were sponsored by British telecoms company Three, but CV members did not like the number being prominently displayed because it reminded them of a rival gang which happened to have the number three in its name: Terceiro Comando Puro (Pure Third Command).

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPunishments for what are considered transgressions are extremely harsh. Being caught stealing can mean losing a hand or being burned alive.

Gang members “sit in judgement” over domestic violence cases and those found guilty are beaten or even executed.

Residents are forbidden from engaging in relationships with members of rival factions or with police officers.

They also know not to photograph or film drug dens or any of the armed men driving through their community.

But with mobile phone use ubiquitous, even gangs as powerful as Comando Vermelho struggle to control what gets posted online.

In Rocinha, a favela under CV control, gang members vowed to kill those who leaked a 2020 video showing a CV leader surrounded by rifles and machine guns.

When someone insists on “causing trouble”, the group often resorts to assault and torture.

PABLO PORCIUNCULA/AFP via Getty Images

PABLO PORCIUNCULA/AFP via Getty ImagesPolice investigation files on Comando Vermelho, seen by the BBC, contain disturbing images.

One shows a woman forcibly submerged in an ice bath, accompanied by a caption accusing her of being “aggressive” and “causing trouble”.

Reports of growing violence and expanding territorial control by Comando Vermelho formed the basis of the complaint filed by Rio’s Public Prosecutor’s Office which led to the massive police operation on 28 October.

And while rights groups labelled it a “massacre” and questioned its effectiveness, Rio de Janeiro State Governor Claudio Castro has announced that more operations against organised crime will follow.

A poll conducted by AtlasIntel suggests that Castro’s approval rating has risen since the raid, and at 47% now stands higher than that of the president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

President Lula, for his part, has announced that the federal government would launch an investigation into the raid.

But in a post on Instagram published on 11 November, Governor Castro said he would “not back down”.

“Law-abiding citizens can’t take it anymore. Rio has fought back – and the whole of Brazil is fighting back with us.”