Jonathan BealeDefence correspondent, Kyiv

Trains no longer run to Ukraine’s eastern Donetsk region – part of the Donbas claimed in its entirety by Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. It’s another sign of the steady Russian advance.

Instead, the last station is now on the western side of the Donetsk border. This is where civilians and soldiers wait for a ride towards relative safety – their train to get out of Dodge.

Putin has been sounding more bullish since the leak of US proposals to end the war, widely seen as being in tune with his maximalist demands. Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky says territory remains the most difficult issue facing US-led peace talks.

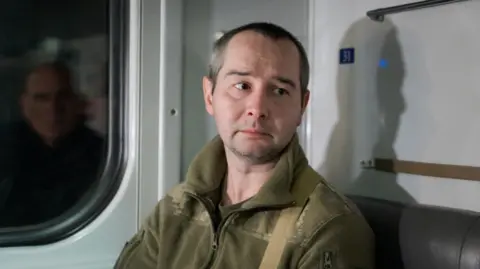

At the last station on the line, soldier Andrii and his girlfriend Polina are parting after an all-too-brief time together. Andrii has to return to the front and they don’t know when they’ll see each other again.

He laughs when I mention peace talks, which have seen Donald Trump’s envoys speak to Ukrainian negotiators before heading to Moscow, and dismisses them as “chatter, just chatter”. He doesn’t think the war will be over soon.

BBC/Matthew Goddard

BBC/Matthew GoddardThere is scepticism, too, among other soldiers who board the train west for a brief respite from the fighting. They are taking some of their 20 days of leave. Most look exhausted.

Russian forces now control some 85% of the Donbas, made up of Luhansk and Donetsk. On Tuesday they claimed to have captured the key strategic town of Pokrovsk in Donetsk. Ukraine said fighting was continuing in the city.

Denys, who has been serving in the Ukrainian army for the past two years, tells me “everyone’s drained, everyone’s tired mentally and physically”.

Some of his comrades have already fallen asleep. His unit has been fighting in the besieged city of Kostyantynivka.

“It’s scary, really scary,” he says, describing drones flying around “like flies”. But he makes it clear they are not ready to give up after sacrificing so much.

“Nobody will give Putin the Donbas. No way, it’s our land,” he says.

Ceding territory where at least a quarter of a million Ukrainians live – the Donetsk “fortress belt” cities of Slovyansk, Kramatorsk and Druzhkivka – will not be acceptable to most Ukrainians.

Russia has spent well over a year trying to capture Pokrovsk and Ukraine is reluctant to hand over such important strategic hubs.

But US officials believe Ukraine is both outnumbered and outgunned.

There’s already been an exodus of civilians from the Donbas. It’s continuing as peace talks take place. We witness dozens, old and young, arriving at a reception centre just over the border in Lozova.

They had taken advantage of heavy fog to make their escape. Less chance of being targeted by drones. Around 200 people arrive at this one reception centre every single day. They’re given basic supplies and some money.

BBC/Matthew Goddard

BBC/Matthew GoddardYevheniy and his wife Maryna have just arrived from Kramatorsk, along with their two children. She tells me there are “more drones now”. “It’s getting harder and harder to even go outside. Everything is dangerous,” she says. “Even going to the shop, you might not come back.”

The family are planning to move to the capital, Kyiv. Yevheniy has little faith in the peace talks. He says “that side [Russia] won’t agree to our terms. We understand nothing good will come of it”.

But others appear more willing to contemplate giving up their home for good in return for peace.

Oleksandr says it is too dangerous to stay. His children have already gone to Germany. While he describes Russia’s maximalist demands as “probably unacceptable”, he appears willing to contemplate some of what was in the leaked peace plan – trading territory for peace. The original version of the US draft envisaged that areas of Donbas still under Ukrainian control be handed over to Russia de facto.

“Personally I would agree to those terms,” he says.

BBC/Matthew Goddard

BBC/Matthew GoddardInna, escaping with her five children, also believes it’s time to make a deal. She could no longer hide her kids, aged between nine months and 12 years, from the dangers of living in Kramatorsk. She had tried telling them the explosions they heard while seeking shelter in their cellar were just fireworks.

“The main thing is that there will be peace,” Inna says. When I ask whether that means giving up her home for good, she replies, “in this situation, yes”. They’re already making plans to rebuild their lives elsewhere.

Some soldiers sent to the Donbas are also voting with their feet. There have been nearly 300,000 cases of desertion, or soldiers going absent without official leave, since the start of Russia’s full scale invasion – and numbers have risen dramatically over the past year.

One of them is Serhii – not his real name. We met him in hiding. His home has become his prison as he tries to evade arrest. Serhii volunteered to fight at the start of the year, whereas most of the men in his unit were forcibly mobilised – “taken off the street”.

He says his unit was already below strength when it was sent to the front, near Pokrovsk, and they weren’t properly trained or equipped. “I ended up in a battalion where everything was a mess,” he says, although he still believes this was the exception, not the norm.

Serhii deserted in May after two of his friends went awol.

“I wouldn’t have gone if we had proper leadership and someone experienced in charge,” he says. “I came to serve, not to run”.

Serhii is still thinking about his next move, and the possibility of returning to the army. But he echoes recent US warnings that the odds in this war are stacked against Ukraine.

Asked whether he believes Ukraine can win, he is doubtful. “If you think logically, no. A country of 140 million against us with 32 million – logically it doesn’t add up.”

Additional reporting by Mariana Matveichuk