“Bust or boom?” That’s the big question at the heart of UBS’ big forecast for the U.S. economy for 2026 through 2028. But the team led by economist Jonathan Pingle also tackles a question that economists have been raising throughout 2025: the fact that tariffs amount to a large tax increase in all but name. Their analysis finds that the tariffs are acting as a substantial drag on growth and are actively contributing to persistent inflation, eroding real income gains for consumers.

“The tariffs are a big tax increase,” the report states simply. According to UBS, the current tariff policies imply a weighted-average tariff rate of 13.6%, based on 2024 import shares, a fivefold jump from just 2.5% at the beginning of the year. This steep rate effectively translates to a tax on imports representing 1.2% of GDP.

The most immediate impact of the trade regime is felt in rising prices, which are “keeping things elevated.” UBS estimates that the new trade regime will add 0.8 percentage points to core PCE inflation in 2026, enough to erase a year’s worth of disinflation progress and keep prices climbing at roughly 3.5% even if other pressures like housing or energy ease.

Over the longer term, UBS expects the tariffs to have a cumulative direct impact of 1.4 percentage points on the level of core PCE through 2028, rising to nearly 1.9 points once knock-on effects like supply chain rerouting and domestic producers raising prices under tariff protection are factored in. Simply: tariffs alone could account for nearly two-thirds of the remaining gap between current inflation and the Fed’s 2% target.

Inflationary Headwinds Hit Households

This tariff-related price pass-through is already translating into pressure on American households. With average hourly earnings growth having slowed to roughly 3.5% annualized over the past six months, and aggregate payroll income running at about 3.25% annualized, this inflationary surge is proving costly. Economists expect quarterly annualized PCE inflation to run between 3% and 4% over the next two quarters, effectively wiping out those income gains.

The report highlights that most households are less able to weather inflation now than they were two years ago. While upper-income households are supported by AI-driven equity market wealth, households below the top 20% of the income distribution suffer from historically low liquid assets. Rising costs, coupled with a slowing labor market, are diminishing consumer perceptions of future prospects.

This headwind is particularly concerning because the U.S. economic expansion is already characterized as “narrowly driven” and “precarious.” The current economic outlook is essentially described as “a big bet on AI,” where the only obvious areas of growth are investment in software and computers (AI-driven) and consumption supported by upper-income equity market wealth. “A decent chunk of the US economy is in recession,” UBS adds, including real residential investment and non-residential construction, is in recession or declining outright.

Returning money back to the people?

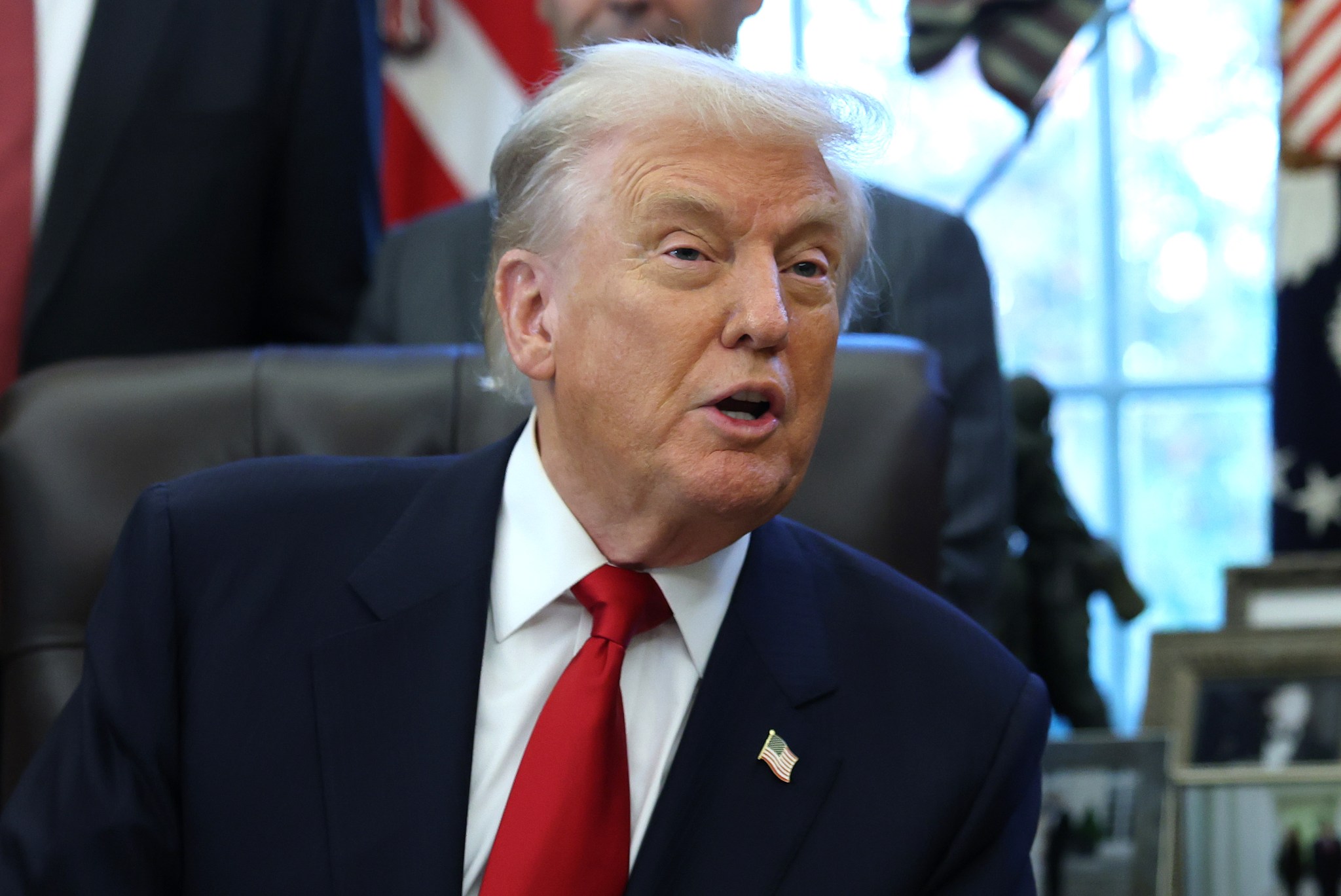

As inflation pressures mount, President Donald Trump is touting his tariffs not only as a shield for American industry but also as a new source of household income. He has floated the idea of a “tariff dividend”—a payout of “at least $2,000 a person (not including high-income people!)”—claiming the surge in tariff revenue is big enough to share directly with Americans.

The headline numbers are certainly striking. The Treasury took in $195 billion in tariff revenue in fiscal 2025, up 153% from $77 billion the year before. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projects that Trump’s broad “reciprocal tariffs” could raise $1.3 trillion through 2029 and $2.8 trillion by 2034. That would lift tariffs from about 2.7% of total federal revenue to nearly 5%, roughly comparable to imposing a new payroll tax or trimming one-fifth of the defense budget.

But analysts say the math behind Trump’s proposed dividend doesn’t hold up. John Ricco of Yale’s Budget Lab estimates a $2,000 payment for every American would cost around $600 billion, far more than the government’s tariff take.

“The revenue coming in would not be adequate,” Ricco told the Associated Press. Even Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent appeared caught off guard, telling ABC’s This Week that he hadn’t discussed the idea with Trump and suggesting any “rebate” would more likely appear as a future tax cut.

Economists also warn that while tariffs generate revenue, they do so by driving up prices. Importers typically pass those costs to consumers, making the policy function more like a regressive tax than a dividend.

Economists find that what’s emerging is a feedback loop: tariffs designed to revive industrial strength are now helping to sustain inflation, which in turn weakens real income growth and constrains the very consumers meant to benefit from the policy. UBS calls it a “narrow expansion,” but it may be narrower still: an economy whose growth depends on circular AI investments and government revenue creation schemes as opposed to the broad spending power of its citizens.